This page documents the investigative steps taken in relation to the fragment PT/35(b) since its alleged discovery on 12 May 1989.

The reader must understand that this is the official timeline reconstructed and wholly accepted by the SCCRC.

=

12 May 1989

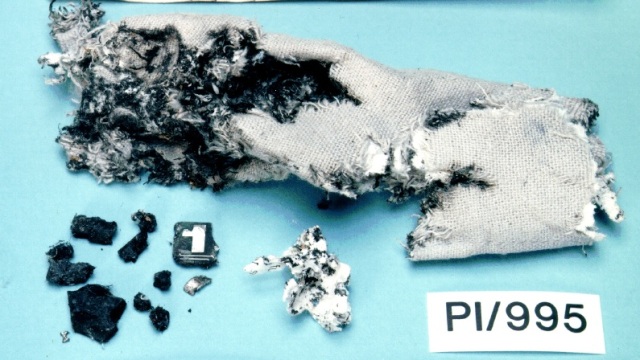

Fragment of circuit board is found in PI/995 by Dr Hayes on 12 May 89, according to

page 51 of Dr Hayes notes. The police production logs for PT/35 record it as having been

found by Dr Hayes at RARDE on 12 May 1989. In his evidence (p2608) Hayes said

he had no memory of finding the timer fragment independent of his notes. In his

chapter 8 Crown precognition (“CP”), Hayes said his recollection was that he worked

alone when carrying out examination of debris, but that he occasionally called Allen

Feraday in when something of interest was found. Feraday in his chapter 8 CP

referred to the discovery of PT/35 and PT/2 and said that he remembered when this was

done. He stated that although Hayes was carrying out the examination, he thought

Hayes invited him in to see the pieces embedded in PI/995 before Hayes removed

them. He stated that Hayes knew he would be interested in what Hayes found, and he

therefore remembered that PT/2 and PT/35 were extracted from PI/995. In his chapter

10 CP Feraday does not specifically mention his memory of PT/35’s extraction. He

states that initially the main concern was with the pieces of cassette recorder manual

that were found in PI/995, as they appeared to support the identification of fragments

discovered earlier, and it was only at a later stage that the potential significance of

PT/35(b) became clear.

22 May 1989

Photo 117 of RARDE report, the first photo of the fragment, was taken on or before 22 May 89, as per photographic register (photo 117 is FC3521).

Summer 1989

According to Feraday’s ch 10 CP, he checked the track pattern of the fragment exhaustively against his database of electronic devices used in explosions but found no match. The precise date and length of time of these enquiries is not specified.

14 September 1989

Visit by Hayes and Feraday to Lockerbie. Feraday viewed items containing circuit boards that were put aside by officers. See Fax 749 in appendix of protectively marked materials.

15 septembre 1989

Feraday sent the Lads and Lassies memo (prod 333, DP/137) dated 15 September 1989 to the SIO along with 4 Polaroid photos that he took himself (prod 334, DP/138). According to the SIO, Henderson’s, HOLMES statement S4710J, during September 1989 he was contacted by Feraday and informed that he had recovered PT/35(b) from PI/995 and he considered it of great significance. Following this contact, Henderson caused Williamson to liaise with Feraday and then carry out the necessary searches of the recovered property and wreckage in an effort to identify the PCB, and he was kept abreast of progress by Williamson.

22 September 1989

Photos 333 and 334 of RARDE reptort – close up photos of fragment, were taken on or before 22 Sept 89, according to the photographic register (FC3877 and FC3878). Photo 333 clearly shows the green colour on the reverse side of the fragment from the “1 ” shaped land.

Some time in September – December 1989 approx

After the Lads and Lassies memo was sent, according to Williamson statement 872BS, a detailed search of productions was carried out to find anything that matched PT/35(b), without success. According to Feraday’s ch 10 Crown precognition, he asked the police to examine all circuit boards that had been recovered and then attended at the production store in Dumfries and examined what the police had found but could find no match for the fragment (this may relate to visit on 14 September 1989, above). See also Henderson’s statement S4710J, which confirms that he instructed Williamson to liaise with Feraday and thereafter to carry out the necessary searches of property and wreckage; the terms of the police report, section 30, which refers to an extensive search and comparison of all other items of circuit board recovered, but no other material relating to PT/35(b) being recovered; and D5609, the memo from Williamson to Ferrie referred to under the entry for 15-18 January 1990, below, which states that a full search of the property store Dexstar was carried out for any circuit board of similar description, which resulted in all items of circuit board including all cameras, radios etc. which contained circuit boards being examined but – nothing resembling the fragment was discovered.

Williamson’s two ch 10 Crown precognitions give the most detail of events at this time. In his ch 10 CP dated 2711 1/99 he states that it was in the days following the receipt of the memo from Feraday that at every opportunity he searched through the productions in an effort to recover all fragments of printed circuit board, including broken cameras etc, in an effort to find a similar board. He states that he set aside a large number of items in the production room i.e. Dexstar, and Feraday then visited there and was unable to locate any boards or fragments that were similar to PT/35(b). He states that at the time the police were working from photos and were also unable to find any boards of a similar description. In Williamson’s ch 10 CP dated 6&7/6/00, it states that Feraday contacted Williamson and said he had identified a fragment of printed circuit board which was unusual as it had “green film” on one side, and Feraday asked Williamson to examine other recovered items to try and identify the source. This initial contact was by phone, and thereafter the memo dated 15 Sept 89 was received. Williamson states that thereafter he personally looked out any recovered items that contained circuit boards, including cameras, radios and pieces of aircraft debris, but he was not able tot find anything similar; and that he recalled that Feraday himself, during one of his visits to Lockerbie, examined a number of these items and was unable to fmd anything that matched.

In his evidence Williamson stated that he informed the team of officers working at Dexstar of Feraday’s memorandum, and that it was obvious that the fragment was important, and to look out for any printed circuit board and extract any such board for Feraday’s examination. Williamson testified that as well as circuit boards, he examined items of electronic equipment – cameras, radios, walkmans, which had PCBs. He confirmed that such items might have been the property of passengers. He confirmed that Feraday came to Lockerbie to carry out these examinations but it was not possible to identify the fragment. Williamson was asked if he could recall over what time period officers in the Dexstar store were examining PCBs and electronic items. He replied that he could not recall exactly, but it was a general instruction, and that he personally withdrew a number of items of PCB himself.

On the basis of fax 749 (see 14 September 89 above) it would seem that a first search for items that might match PT/35(b) took place before 15 September 89, as on 14 Sept 89 Feraday examined items looked out by the police. However, it seems apparent fiom fax 749, the lads and lassies memo and Williamson’s accounts that the search for items at Dexstar continued thereafter.

Williamson’s CP goes on that in October or November 89 he was part of a team reviewing BKA reports on the Autumn Leaves enquiry and that in January 1990 he accompanied Feraday to Germany to view items recovered by the BKA in that operation. Although not stated expressly in the CP, it seems apparent that this exercise of reviewing BKA material is what led to the suggestion that Feraday examine the recovered items from the BKA operation to compare to PT/35(b). (See more under January 1990, below).

19 December 1989

There is a memo from McManus to Williamson (D5441 – see appendix to chapter 8 of the statement of reasons) dated 19.12.89 re a phone call McManus had with Feraday during which McManus requested a meeting at RARDE to discuss “recent and potential developments concerning PT30 – piece of circuit board of uncertain origin – and obtain as much information and opinion of this item as possible.”

Feraday replied that he had already discussed the matter with senior management at Lockerbie and saw no benefit in further discussion. McManus pressed him and referred to other potentially significant blast damaged items, and to items found in a search of Abassi’s flat in Germany, but Feraday did not agree to a visit to RARDE.

There is another memo of this date from Williamson to Henderson (D5428 – see appendix to chapter 8 of the statement of reasons) re “item of interest at RARDE – circuit board”. Reference in the memo is again to PT/30, which is said to have been found in PK/2128, part of an American Tourister suitcase, at RARDE on 18 June 1989 (which would be consistent with PT/30, except it was found on 8 June, not the 18th).

The memo says Feraday regarded this find as potentially most important and photos and a description of the item were supplied to the productions/property team to allow a full search at Dexstar for similar material [this sounds like it is referring to the Lads and Lassies memo]. It is stated that on 14 September 1989 Feraday visited Dexstar and examined various items there but none matched PT/30 (see fax 749), and on a number of occasions he has expressed interest in any circuitry that could be compared to PT/30. Reference is then made to items recovered from Abassi’s flat in Germany, and in particular digital alarm clocks and circuit boards, and it is suggested that these items be secured for scientific examination.

Much is made in the submissions about the latter memo above, and it is submitted that originally PT/30 was unidentified, and the Lads and Lassies memo referred to it, but when PT/35(b) was reverse engineered into the chain of evidence, the memo about PT/30 was said instead to have been about PT/35(b), in order to make it look like it had been there from the start. This matter is addressed in chapter 8 of the statement of reasons.

10 January 1990

The fifth internatonal conference took place at Lockerbie. The minutes for this meeting are contained in Volume D of the application, at footnote 347. There is no specific mention of any fragment of circuit board in the minutes. A further copy of these minutes was obtained from D&G. Again, there is no mention of the circuit board fragment.

15-18 January 1990

According to Williamson’s statement S872BS, he and Feraday went to Meckenheim

where they examined a large no. of electronics including PCBs recovered in antiterror

operations, but no items resembling PT/35(b) were found.

There is a further memo, D5609, from Williamson to Fenie, which is undated but

apparently compiled shortly after the visit to Germany, and it gives a detailed account

of the unidentified fragment, which is now referred to as PT/35 (although at one stage

is also called “PF 35” which is presumably a typo) and is said to have been recovered

from a fragment of shirt material described as “PA995” (presumably another typo).

Reference is made to Feraday frequently expressing interest in identifying the

fragment, and to the fact that after a Sunday Times article on 17 December 1989 he

“firmed up” his interest by stating that in his opinion the fragment could be part of the

IED timing mechanism. Reference is then made to the Autumn Leaves papers

indicating that various circuit boards etc were recovered, and that from Monday 15

January 1990 to 18th Williamson and Feraday went to Wiesbaden, BKA HQ, and to

Meckenheim to examine and photograph these items and compare them to PT/35 and

all items except a “Krups clock” were eliminated, the clock could not be eliminated as

the circuit board had been removed. The memo indicates that the Germans were

looking to obtain an identical clock or schematic diagram, and it is suggested that a

Lockerbie officer should also do this.

The document then gives a detailed description of PT/35, including its dimensions,

the fact that it is made of fibreglass, that its tracking pattern is of tinned copper and

not lacquered, it has a curved and a smooth edge that were manufactured; and it is

suggested that Feraday said discovering the origin would be a huge if not impossible task.

A separate memo from Williamson to the SIO dated 16 March 1990 which formed a

report on the fragment (and which is mentioned at various places below) documents

the outcome of the “Krups” enquiry. According to this memo, from LICC enquiries were

made with Krups, which led to the manufacturer, then the supplier of the works

for the clocks, and then the supplier of the original circuit boards, a company called

Moker. Moker advised that the board contained in the particular Krups clock found in

the Autumn Leaves raids was made with Phenolic paper and not fibreglass, but

supplied to LICC a complete range of all circuit boards they manufactured, and the

sample that was contained in the clock in question bore no resemblance to PT/35(b).

There is also a fax from Feraday dated 16 February 1990 confirming no match

between the fragment and the Krups circuitry.

In Williamson’s ch 10 CP dated 6&7/6/00 he says that in October and November

1989 he was part of a team reviewing BKA reports on Autumn Leaves and that in

January 1990 he went with Feraday to Meckenheim to view the items the BKA had

recovered in the Autumn Leaves operation, including bomb making equipment.

Williamson stated that he particularly recalled a Krupz clock (although the memo

mentioned in the preceding paragraphs suggests that the circuit board had previously

been removed from this clock) and various printed boards, none of which matched

PT/35(b). He stated that he vaguely recalled that the items involved in the death of

the BKA officers during Autumn Leaves were shown, but could not recall specific

details.

In his evidence Williamson added little about the trip to Germany, confirming that

Feraday took the lead in examining the items but that nothing similar to the fragment

was found.

Papers relating to this trip to Meckenheim were obtained from D&G. One is the

report by Williamson, D5609, the contents of which are reproduced in D&G’s letter

and which are mentioned above (a copy had already been obtained from the files held

at Dstl). Then there is another report by Williamson, D5486, re a visit to RARDE

during which PT/35 was discussed and it is referred to as recovered from PI995. The

report then lists a Q&A with Feraday re the fragment of circuit board, re what other

enquiries could be conducted should the fragment not match samples recovered by the

German investigation. The report is dated 8 January 1990 and relates to a visit to

RARDE on 5 January 1990. D&G also provided an action form for the trip to

Germany, the result of the action is dated 16/1/90 and specifically refers to production

PT35 and the result being negative. There is also a fax from Feraday of 16/2/90

confirming that PT/35 did not match the circuit board in the Krups clock.

20-22 January 1990

In a letter to Feraday from Gordon Ferrie dated 20 January 1990 (an initial look at the

date might lead one to believe it is 2 January, but it appears there is a small “0” to

make it 20 -the letter must post-date the trip to Germany by Williamson and Feraday,

as this trip is referred to in the letter, so it seems the date must be the 20) reference is

made to the negative results from the examinations in Germany and it is requested

that Feraday fax the SIO with a report on the circumstance and importance of the

fragment (which is not named) so that consideration could be given to investigating

the fragment, which would involve committing considerable resources and manpower

for an indefinite period (see chapter 8 appendix).

Ferrie’s letter appears to be what prompted Feraday’s faxed memo of 22 January 1990

(prod 1761, DC/1802), although Feraday’s memo refers to him being in receipt of a

fax from the SIO of that date, 22.1.90. A request was made to D&G for a copy of the

SIO’s fax, and D&G’s response was that the only document that could be traced that

is linked to Feraday’s memo is the letter from Ferrie to Feraday, which D&G suggest

is dated 2 Jan 90; D&G state that these two documents were attached to each other in

the HOLMES system, under the same document reference.

Feraday’s memo contains an account of the history of the fragment, including its

recovery from PI/995 and the significance of this, given the apparent proximity of that

fragment to the explosion, and given that the circuit board fragment is also blast

damaged. Feraday’s memo suggests that the fragment could be part of the IED

mechanism/circuitry and if so would be the only piece of mechanism recovered. He

refers to having attempted to provide a “flying start” to enquiries into the fragment but

that he had so far drawn a blank, and he advises that resources be committed to

identifying the fragment.

The submissions suggest that this memo is indicative that PT/35(b) was only

“discovered” in January 1990 because the memo says “Item PI995 originally

consisted of a charred fragment of grey material which is now known to have been

part of the grey ‘Slalom’ brand shirt” (emphasis added); and later, after listing the

items removed from PI995, says that these items are “now isolated from PI995 and

are collectively now identified as PT35” (emphasis added). This issue is addressed in

chapter 8 of the statement of reasons.

According to the police report, on 22 January the SIO instructed Harrower and

Williamson to dedicate enquiries to identification of the fragment PT/35.

Williamson’s statement BS states that this instruction was issued after a memo from

Feraday re PT/35(b) (which is presumably the memo referred to in the preceding

paragraphs). The SIO’s statement S4710J states that on 22 January 1990 following

further contact with Feraday regarding the fragment of PCB, PT/35(b), and its

potential evidential value in that it could have formed part of the detonating

machinery of the IED, he instructed Williamson to dedicate himself totally to the ID

of the fragment. The statement says that in the following months the SIO was

frequently updated by Williamson as regards the progress of enquiries, which related

in the main to the physical structure of the fragment.

The submissions to the Commission refer to three other documents, apart from

Feraday’s memo of 22 January, that indicate that PT/35(b) was only first discovered

in January 1990, and perhaps on 22 January 1990. This issue is addressed in chapter

8 of the statement of reasons.

NB It is apparent from the Grand Jury testimony of Tom Thurman (prod 1743) that at

some stage before June 1990 he received a copy of Feraday’s memo dated 22 January

1990.

23 January 1990

Having been instructed by the SIO to investigate the fragment of circuit board,

Williamson spoke to George Wheadon, Chief Technical engineer, New England

Laminate Co., Skelmersdale (see 26 Jan and 14 Feb, below) for the first time seeking

help in identifying the circuit board and Wheadon agreed to assist (according to

Wheadon’s statement S5576, although no mention is made of this initial contact in

Williamson’s statement or in Harrower’s). In Williamson’s ch 10 CP dated 2711 1/99

he states that the reason this company was chosen for the initial contact was because

the police decided to first select companies near Lockerbie.

25 January 1990

Harrower (S929AC) collected PT/35(b) from Goulding (RARDE police liaison

officer) at Heathrow airport. This is confirmed by a RARDE note (a copy of which

was obtained from the Dstl files) which appears to be in Goulding’s handwriting and

appears to be signed by Harrower, which simply records that the signatory received

production PT/35; and also by McManus’s movement records (DP/29), and the

production logs, which record 25/1/90 as the first date PT/35 was received back from

RARDE; and RARDE’s formal records of movements (obtained from Dstl). In

Williamson’s ch 10 CP dated 6&7/6/90 he states that his recollection was that he and

Harrower both collected the fragment from Goulding at Heathrow. There is no

mention in Williamson’s HOLMES statement of him having done this, nor is there

mention in Harrower’s HOLMES statement or his ch10 Crown CP that Williamson

was present.

26 January 1990

Williamson (BS) and Harrower (AC) met George Wheadon at LICC by previous

arrangement; Wheadon carried out initial microscopic examination of PT/35(b), said

it had been subjected to severe heat and flame, the surface had been brushed then

scratched after manufacture, the curved edge was milled rather than punched

suggesting it was made by a fairly good manufacturer, and it was constructed with

nine layers of glass cloth. (According to his defence precognition and his evidence,

Wheadon rubbed down an edge of the fragment to make the layers visible, but he said

in evidence that this had no material effect on the appearance of the fragment; an

additional note refers to him being precognosced at Zeist and being unable to identify

which edge of the fragment he rubbed down at Lockerbie from prod 335 photo, and

stating that he apparently did this using a matchbox, and the most likely area was

what is now DP111 (i.e. the strip cut from the top of the fragment, see below);

Williamson in his ch 10 CP dated 6&7/6/00 stated that he had no recollection of

Wheadon doing anything with the fragment at this stage). According to both of

Williamson’s ch 10 CPs, Wheadon also said that the 9 layers were unusual, and that 8

layers was more common. In the CP dated 17/11/99, Williamson says Wheadon

thought 9 layers was more common in Italy. Wheadon’s own CP concurs with this:

he stated that most manufacturers produced 8 ply boards and he only knew of two

manufacturers, PIAD of Italy and Sefolam of Israel, that produced 9 ply boards

although there could have been others. He also said that 5 to 10 years prior to his

examination, 9 ply was more common. He said that he advised the police to

concentrate on identifying the manufacturer in Southern rather than Northern Europe.

However, Wheadon’s defence precognition states that he also advised the police to

contact Exacta Circuits, Selkirk, who manufactured circuit boards. It is not recorded

in any HOLMES statements, but in a report on PT/35 that was obtained from the Dstl

files, which is basically a memo from Williamson to the SIO dated 16 March 1990, it

lists all the places that Williamson visited and Exacta is mentioned (see 29 Januaty

1990, below).

According to Williamson’s CP Wheadon suggested further lines of enquiry including

identifying the manufacturer of (1) the fibreglass laminate, (2) the copper foil and (3)

the solder mask. Wheadon advised that testing could be done but would involve

changing the fragment’s physical appearance. According to Williamson’s ch 10 CP

dated 2711 1/99, after Wheadon said this, the SIO was consulted and it was agreed that

samples could be removed from the fragment. None of the examinations were to be

carried out outwith the presence of the police officers, none of the examinations were

to be “all consuming” and Williamson was to ensure that he recovered both the

fkagment of circuit board and the sample which had been removed from it at the end

of each test. In Harrower’s ch10 CP, he states that whenever he and Williamson were

away overnight with the fragment, it was sealed in a bag and retained at the local

police station for security.

29 January 1990

(“other enquiry” i.e. not evidentially significant)

In Williamson’s memo to the S10 dated 16 March 1990 (the contents of which are

repeated and updated in a further memo of 3 September 1990 – as these memos were

obtained from Dstl, HOLMES document numbers are not known) he listed “other

enquiries” that were carried out duning the course of enquiries into identwg the

fragment. The first “other enquiry” is listed as a visit to Exacta Circuits, Selkirk

(PCB manufacturers) on 29 Jan 90, where the fragment was discussed with Ian Laing [a

and Colin Gass, technical director and technical manager respectively. There do not

appear to be any HOLMES statements for these individuals, nor any other details of

what the visit entailed.

8 February 1990 (removal of first sample – DP/12 (Crown label n°414) – pin head

size sample – resin test)

By previous appointment Williamson and Harrower attended Research Analysis Dept,

Ciba Geigy plc, Duxford, Cambridgeshire, and met John French (S5583, although

French’s ch10 CP suggests they did nlot have an appointment). French had agreed to

assist by carrying out tests to try and identify the type of resin used in the manufacture

of the fibreglass, and he was permitted to remove from one edge of the fragment a pin

head size sample for analysis. According to statements the removal of this sample did

not change the shape or size of the fragment. The pin head sample was designated

DP/12. According to French’s statement he noticed that PT/35(b) appeared to have

been subjected to heat damage and appeared charred at the edges and advised that it

would not be possible to positively identify something which had been subjected to

large heat exposure when comparing it to something not subjected to such heat, as the

heat changes the molecular structures. According to the HOLMES statements French

examined DP/12 with an infrared spectrometer and produced DP/18 – spectra

printout, but in fact this should red DP/139, prod 338: DP/18 is a later spectra

printout produced by French on 8 March, see below. It is clear from the CP of John

French that he clarified this with the Crown. (In Williamson’s ch 10 CP dated

6&7/6/00 he states that he cannot explain why the police number, DP/139, is so high,

he states that he was not responsible for the police numbering and that it was done by

the production officer at a later date. In his chlO CP Harrower was also asked about

this, and it was pointed out to him that the contents of DP/139 pre-dated those of

DP/18, but Harrower said he did not know why the numbers were listed in this

fashion, and said he could no longer recall whether the first printout received from

French, DP/139, was sent by French through the post, although he did recollect that it

was decided following the visit to Ciba Geigy that all documentary productions

produced during examinations would be seized immediately. Harrower also noted

that he had not signed the label for DP/139, although Williamson and French had).

French concluded that the board was made with bisphenol A epoxy resin, which was

commonly used.

In his ch10 CP French stated that he was used to examining PCBs as companies

would come to Ciba to analyse boards. He told the officers on their first visit that it

would not be possible to identify a manufacturer of the board. He described the test

he did on DP/12. He confiied that he signed the labels for DP/12 and PT/35(b) and

when shown them he recognised both fragments, noting that PT/35(b) had been

further altered since he saw it. As stated above, he also clarified that DP/18 was the

spectra printout he produced after the second visit of police (see 8 March, below) and

that DP/139 was the original spectra printout. He stated that he recognised his work

in DP/139, and therefore signed the label for it at the precognition, having already

signed DP/18 at the time the police were there. In his ch 10 CP dated 1711 1/99,

Williamson states that following the examination by French, Williamson was of the

view that it would be beneficial to pursue the ID of the resin and he instructed

Harrower to obtain samples of circuit board from the major producers throughout the

world. (See more under 8 March 90, below.)

NB John French was also seen by police in 1992 and asked to examine a control

sample MST-13 circuit board – see 4 March 1992 below. Note also that inspection of

the police labels

12 February 1990 (photo of PT/35(b) – DP/140 (prod 335) / prod 1754)

Williamson and Harrower attended at the photographic department at Strathclyde

police and arranged for PT/35(b) to be photographed in studio conditions, in order to

preserve for evidence a record of its physical appearance to allow for any future

comparison. According to the officers’ HOLMES statements, the photographs taken

by Roderick MacDonald (S1892BK) there were designated DP/140 (prod 335). In

fact this production is just a single close-up photo of the fragment. It is apparent from

his ch10 CP and his evidence that there were a number of photos of the fragment

taken by MacDonald at this time, and that a selection of these were contained in a

book of photos that formed prod 1754 (police ref CS124). From its appearance,

DP/140 was just a copy of one of these photos. According to MacDonald’s ch10 CP,

the master film for the photos in prod 1754 was numbered 9920 (which cross-refers to

the number on the front cover of prod 1754) and this film formed prod 1753 (police

ref CS1122). In his CP he stated that he had taken the photos in prod 1754 using a

“Macro lens”. He confirmed that he wrote the details on the booklet and that he was

satisfied that the film prod 1753 corresponded to the photos in prod 1754. The

flipdrive image of prod 1753 only depicts the negatives for a small number of the

photos, and the Commission’s hard copy productions do not contain photocopies of

the negatives, but given the contents of MacDonald’s ch10 CP and what can be seen

on the flipdrive of prod 1753, it seems clear that prod 1753 does indeed comprise the

negatives for prod 1754. In evidence MacDonald noted that he had not signed the

label attached to prod 1754 (it was apparent that it was only attached during the

preparations for trial), but he accepted that the date on the front cover of booklet,

12/2/90, was correct. [NB note also that in MacDonald’s chlO CP the fiscal who

inserted in handwriting the production numbers of the photos and negatives

MacDonald was shown got the number 1752 mixed up with 1754, and 1753 mixed up

with 175 1. The mix up relates to later photographs taken by MacDonald of the timer

fragment – see under 17 May 1990, below.]

DP/12 was the only sample removed from PT/35(b) prior to this photo being taken.

According to the relevant witnesses the appearance of the fragment was not altered by

removal of the sample.

In the submissions to the Commission it is questioned who took this photograph and

why the fragment required to be photographed in Glasgow in February 1990 if it was

recovered in May 1989. The answer to the first question is contained in MacDonald’s

defence precognition and in his trial evidence, so should have been clear to the

defence. As for the reasons why it was necessary to photograph it, although there are

close-up photos of the fragment (photos 333 and 334 of the RARDE report) which are

dated September 1989 (above), it seems to be a sensible investigative step for the

police to have obtained a photo of the fragment before samples were removed fiom it

(especially if, as seems possible, they were not aware of the close-ups already taken

by RARDE, which were produced after the lads and lassies memo was sent). In a

memo from Williamson to the S10 dated 3 September 1990 (which is basically the

original memo of 16 March 90 with extra information added in) reference is made to

the photographing of the fragment on 12 February 1990. It is explained that at an

early stage in the investigation it was repeatedly opined by all technical persons who

assisted with preliminary assessments that test samples would have to be removed

from the fragment, and that prior to (any such samples being taken, it was necessary

that good quality photographs be taken of the fragment to record its original shape and

condition to allow future comparisons to be made with any similar PCBs or other

fragments, and that his was done on 12 Feb 90 under laboratory conditions at

Strathclyde police.

13 February 1990 (“other enquiryn i.e. not evidentially significant)

According to Williamson’s memo of 16 March 1990 to the S10 another of the “other enquiries” that was carried out was a visit to RS Components Limited, Corby, on 13 Feb 90 where the fragment was shown to unnamed members of technical and product support staff. Certain observations and suggestions were apparently put forward as to the possible identity and function of the circuit on the board but no definite information was received. There is no other information about this visit.

14 February 1990

Removal of 2nd sample – DP/11 (Crown label n°.415) – strip above “1” – laminate test

Williamson and Harrower attended at New England Laminates, Skelmersdale, and

met George Wheadon again, to allow him to examine PT/35(b) thoroughly in lab

conditions. DP/11, a cross section sample, was removed from PT/35(b) and was set

in a potting compound to allow it to be viewed microscopically in cross-section. Paul

Boyle (S5577), laboratory manager, cut DP/11 fiom PT/35(b) (in his evidence

Wheadon confirmed that he had signed the label for DP/11). According to Boyle’s

defence precognition the cut was done in front of the officers using a low speed saw,

and he also describes in detail the process of setting the sample in the potting agent

and grinding and polishing it down to get a clear image. Wheadon and Boyle

confirmed the fragment was nine layers of glass cloth, with solder mask on the

underside but they could not be sure if it was a double-sided board [i.e. if it had

tracking on both sides] (although in his CP dated 4/8/99 Wheadon says he thought it

probably was double-sided, based on the presence of solder mask on the underside

and that most material produced at the time was double-sided). They said it was from

an “FRY type board (fire retardant value) of standard thickness (1.6mm) including

the copper cladding and the glass cloth was American designation 7628, which was

very common. The copper tracks were plated with what appeared to be tin lead.

Wheadon took Polaroid photos of DP/11, the first photo showing the top layer of tin

lead, the second layer of copper foil and the remaining nine layers of glass cloth; the

second photo showing a close up of the tin lead and copper foil, and the third showing

the middle line solder mask. These photos were given the designation DP/19 (prod

339, the police label for which was filled out and signed by Harrower, according to

his ch10 CP; according to Wheadon’s CP dated 4/8/99 and Boyle’s CP dated 2/3/00,

they signed the label for DP/19; in evidence Wheadon said he thought Boyle had

taken the photos, although other indications are that it was Wheadon). (In his

defence precognition Boyle examined the photos in DP/19 and said that “Middle-Line

Solder Mask” meant nothing to him at that time and the quality of the photo did not

help him, although as he signed the label he thought it must have meant something to

him at the time.)

According to Wheadon’s defence precognition and evidence, 9 layers of cloth was

unusual in that the industry standard at the time was 8 layers, and he thought a

company, Piad in Italy still used 9 layers, but other manufacturers might have

remaining stocks of 9 layers. (This seems roughly consistent with Williamson’s

memory, as recorded in his ch 10 CPs, except that Williamson thought Wheadon said

these things after the initial meeting on 26 January (above). Likewise Wheadon’s

own CP dated 4/8/99 seems to suggest he said these things after the initial meeting.)

Williamson’s ch 10 CPs record only that it was established by Wheadon after the

examination of DP/11 that the copper was standard one ounce weight.

One thing of note in Paul Boyle’s CP dated 2/3/00 is that he states that a few weeks

after this visit, the police returned with DP/11 and it was clear that the sample had

been examined by someone else. It had been altered, the potting compound had been

further ground down and the sample was now sitting at a 90 degree angle. He

examined the sample in its new state and saw nothing which altered his previous

conclusion. He stated a similar thing in his defence precognition, stating that whoever

had altered DP/l l must have known what they were doing and would have been an

expert. The Commission has seen no record anywhere else of the police returning to

New England Laminates. However, it appears that they must have done so, given

Boyle’s very specific recollection of the changes to DP/11. The changes he describes

appear consistent with what Allan Worroll of Ferranti did to DP/11 on 11 April 1990

(see under that date, below), indicating that the return visit to New England Laminates

must have been some time after that.

[Re DP/11, note that Feraday sent a memo to the SIO on 8 July 1991 (see under that

date, below for more details on this) suggesting that he did not think DP/11 originated

from PT/35(b).] NB Note also that Boyle’s signature appears on the label for DP/11

although it is difficult to identify Wheadon’s in the labels for DP/11 and PT/35(b) and

Boyle’s signature in the PT/35(b) label.

15 February 1990

Removal of 3rd sample – DP/10 (Crown label n° 416) –

sample of copper conducting track – copper test

By previous appointment Williamson and Harrower visited Yates Circuit Foils,

Silloth, Cumbria, and met Michael Whitehead (S5587), chemical process manager,

who analysed the copper foil used to manufacture the board from which PT/35(b)

came. Whitehead removed from PT/35(b) a tiny (in his defence precognition and his

evidence Whitehead said the sample was about lmm X 3mm and triangular in shape,

visible to the naked eye) fragment of copper conducting track, designated DP/10, and

it was treated for microscopic examination (an account of this treatment is contained

in Whitehead’s defence precognition) and positioned on an examination stud, and

microscopic examination of the “matt side topography7′ on the underside of the

sample was carried out and comparison made to samples of copper foil produced by

Yates and by their main competitor, Gould Electronics (see below). According to his

HOLMES statement, Whitehead’s conclusion was that the copper was produced by

Gould Electronics because of the appearance of the “Dendritic structures” in the

copper. He suggested that the copper was made around 5 years previously, as around

that time the dendritic structures in the copper produced by Gould changed.

However, Williamson and Harrower’s HOLMES statements suggest that Whitehead’s

conclusion was that the copper was made at most 5 years ago, which seems slightly

different from “around” 5 years ago.

In his evidence Whitehead said that he was able to tell the police his own company

had not manufactured the copper and said he was able to identify an alternate source

but could not be definitive – presumably he meant the alternate source was Gould

(although note the comment in his CP below). He was not asked for any more detail.

However, in his defence precognition Whitehead said that he had concluded that

neither Yates nor Gould had manufactured the copper, and that he thought it looked

like Far Eastern technology. Whitehead was not cross-examined at all. In

Williamson’s ch 10 CP dated 6&7/6/00 it is recorded that Williamson’s understanding

was that Whitehead thought that Gould had manufactured the copper, and the PF’s

note states that this contrasts with Whitehead’s precognition. In his CP Whitehead

said that the sample he examined was not made by his own company and he did not

think it was manufactured by Gould either, but it could have been an old Gould

sample. He said in his opinion the sample was manufactured in the Far East i.e.

Japan, and he recommended that the police concentrate enquiries to ID the

manufacturer of the copper there. He said he had no recollection of telling police that

the copper was produced by Gould and if he did say this it was incorrect. A note by

the precognoscer points out the inconsistency between Whitehead’s position and that

of Harrower’s statement, and says that Whitehead’s view is that Harrower’s statement

is wrong and he gives a “convincing explanation” in support of the Far East theory,

referring to the pyramid features shown in the micrographs. The note points out that

the defence are aware of the discrepancy. It also points out that the manuscript police

statements for this part of the enquiry cannot be traced. Williamson’s CP then states

(presumably after being asked about it) that he vaguely recalled there being some

discussion regarding the Far East, in conversation, but that he did not recollect

Whitehead concluding that the foil had been manufactured in the Far East.

It seems clear from this and from the terms of Whitehead’s DP that, prior to trial,

Whitehead’s recollection was that the copper had been manufactured in the Far East.

Harrower’s ch10 CP is similar to Williamson’s, in that it states his recollection to be

that Whitehead felt the copper foil had not been manufactured by his company but

had most likely been manufactured by Gould. During his original examination of

DP/10 Whitehead produced 6 close-up Polaroid photographs showing the different

Dendritic structures, and these photos were designated DP/14 (prod 340, the police

label for which was completed and signed by Harrower, according to his ch10 CP;

Harrower noted but had no explanation as to why Whitehead had not signed this

label). NB according to a note added to the HOLMES statement of Whitehead,

subsequently DP/10 became detached from the stud mounting during an examination

by Robert Lomer (see 7 March 1990 below) and because of its minute size, was lost.

In evidence Whitehead was shown DP/10 and said he did not think he could see the

sample on the stud.

NB Michael Whitehead was also seen by police in 1992 and asked to examine a

control sample MST-13 circuit board – see under 6 March 1992, below. NB It is

difficult to identify Whitehead’s signature on the label for DP/10, or on the label for

PT/35(b).

16 February 1990 (“other enquiry” i.e. not evidentially significant)

According to Williamson’s memo of 16 March 1990 to the S10 another of the “other enquiries” that was carried out was that contact was made with Roy Hollaway of DuPont, UK (Solder Masks) on 16 Feb 90, who advised that they had no proper lab facilities in the UK but gave some information and advice. There is no HOLMES statement for Mr Holloway and the Commission has seen no other information about this visit.

20 February 1990 (“other enquiry” i.e. not evidentially significant)

According to Williamson’s memo of 16 March 1990 to the S10 another of the “other enquiries” that was carried out was that contact was made with Mike Gower at the British Standards Institute but he was unable to assist in the enquiries. There is no HOLMES statement for Mr Gower.

20-23 February 1990

A liaison meeting took place between British and French during which the French

scientist Claude Calisti was shown PT/35(b) but could offer no assistance or

suggestions. See document D8924 in appendix of protectively marked materials.

According to Langford-Johnson’s police notebook (prod 1766, pages 8-9), on 4

February 1991 he and Williamson went to the Central Explosive Lab in Paris with a

view to showing photographs of the timing device MST-13 to senior forensic

scientists and to see if the device was known to them. The notebook records that they

spoke with Claude Calisti, who said he “was aware of the line of investigation being

undertaken in relation to PT35 having been at an earlier briefing on 28.2.90”.

Presumably this in fact relates to the meeting on 20-23 Feb 90.

2 March 1990

Metallurgy test and report. No samples removed

Williamson and Harrower attended the Bio-Engineering Dept of Strathclyde

University by previous arrangement and met with Dr Rosemary Wilkinson (S5579)

(Whitehead in his defence precognition said he recalled suggesting to the officers that

they try Strathclyde Uni; in her defence and Crown precognitions Dr Wilkinson said

the officers arrived out of the blue, but might have been referred to her by her

superior), to gain more information about the silver coloured metal that overlaid the

copper conducting tracks and land on the fragment.

In her HOLMES statement Wilkinson states that she examined the metallic areas of

the fragment microscopically and found that the two parallel bars showed the presence

of copper and tin and in some places only copper, which would be consistent with the

parallel tracks having originally been coated in tin but some of the tin subsequently

having been removed.

She stated that on the pad (the “1” skape) she found copper, tin and lead, which would

be consistent with a layer of solder having been overlayed to the previous structure of

copper coated by tin. She found some areas of the land to have little or no lead,

suggesting either that the solder had been melted, uncovering these regions, or that

solder was applied manually to the pad but not to the regions where there was little or

no lead. She provided metallurgy printout data which was designated DP/21 (prod

343) and 7 photographs produced in her test machinery, designated DP/20 (prod 344),

the police label for which Harrower in his ch10 CP noted had not been signed by

Wilkinson, but he could not offer any explanation as to why. According to

Williamson’s memo of 16 March 1990, Dr Wilkinson also stated that she saw at the

bottom left hand corner of the pad a lead rich area with a diagonal marking that

appeared to be a section of a cylinder, which she said could possibly be the remnant

of where wire was embedded in the solder.

In his memo to the SIO of 16 March 1990, Williamson states that the fact that it was

only tin as opposed to tin/lead that coated the tracks was, without exception, regarded

by all the experts they visited as being the most interesting feature, as it was unusual.

The memo states that in furtherance of this information an examination was carried

out to establish the thickness of the tin. This was done by Digital Equipment

(Scotland) Limited using Fischer scope XRF and measurements were taken at various

points, which showed the tin varied in depth from 1.41 microns to 4.57 microns.

There is no further information about this test, the date it was done or about who

carried it out. The memo also states that enquiries were made with numerous

companies in the UK in an effort to learn more on the use of tin in these

circumstances but the enquiries proved negative, there being no companies known in

the UK who continue to use pure tin in the way that it had been applied to PT/35(b).

Again, there are no further details about these enquiries in the memo.

In her defence precognition Dr Wilkinson mentioned having done various

examinations including x-ray examinations. She suggested that the officers seemed to

want to know whether the fragment had been involved in an explosion, and her

opinion was that, while she noticed some changes to the metal, she did not find

anything that would specifically indicate it was involved in an explosion e.g.

abrasions to the surface of the metal parts or loss by melting. She could not say for

certain whether or not it had been in an explosion. She was precognosced a second

time by the defence on 1 June 2000, apparently because of her comments about the

absence of evidence of explosion damage, and she went into greater details about the

various tests she conducted. There are also papers in the McGrigors files in which the

possibility is discussed of calling Dr Wilkinson for the defence, given her position

that there was no evidence to confirm an explosion. However, it was agreed that she

accepted she lacked expertise in this area (i.e. in explosion damage and in PCBs), and

it was agreed that she should not be called as a witness. In her CP she stated that the

test of one the copper tracks revealed a high ratio of copper and no lead, and that on

the land, there was no consistency in the ratios of copper, tin and lead in the five areas

tested. She later stated that she would expect to see these three elements on the land,

as it would be consistent with a layer of solder being overlayed on a copper base, but

she would expect the ratios to be fairly uniform when produced by the manufacturer,

whereas on the fragment certain areas showed little or no lead at all. She suggested

this could be due to errors in manual application of solder or partial melting of the

solder, uncovering the copper below.

NB Dr Wilkinson was also seen by police in 1992 and asked to examine a control

sample MST-13 circuit board – see 28 Feb 1992 below. NB Wilkinson’s signature is

visible on the label for PT/35(b).

6 March 1990

“Other enquiry” i.e. not evidentially significant

According to Williamson’s memo of 16 March 1990 to the SIO another of the “other enquiries” that was carried out was a visit to Prestwick Circuits, Ayr (PCB manufacturers) on 6 March 1990. Excellent co-operation and advice was apparently received during discussions with senior management and technicians, and their conclusions were that the board had been professionally manufactured but not to a high standard and using dated technology.

They suggested the best line of enquiry to be that the tin which was used as an etch resist (i.e. that coated the circuit board tracks) was uncommon as was the 9 layers of glass cloth, so these were the best avenues to pursue.

Harrower’s defence precognition demonstrates that he did not have a good memory of the various places that he visited when enquiring into the source of the fragment. However, he did mention that Prestwick Circuits rang a bell.

7 March 1990

Removal of 4th sample – DP/15 (Crown label n°.417) – sample of copper conducting track

Williamson and Harrower attended at Gould Electronics, Southampton, to allow them

to examine DP/10, previously removed by Yates, to try and confirm that Gould had

manufactured the copper. In the HOLMES statement of Robert Lomer, Quality

Assurance manager, he stated that it was explained to him by the officers that Yates

had identified the copper as possibly manufactured by Gould. Lomer microscopically

examined the examination stud on which Whitehead had fixed DP/10, but Lomer

could find no trace of copper there, so concluded that it must have become detached and was lost.

He therefore removed another sample of copper conducting track,

designated DP/15 and prepared it for examination, but found that when removing the

copper sample a part of the fibreglass laminate had remained adhering to the copper

sample, which rendered examination impossible, and because of the size of PT/35(b)

he was not confident he would take another sample without significantly damaging the

fragment. He therefore could not confirm whether Gould had made it.

At Crown precognition, while he was able to say that he removed the further sample, DP/15, from the fragment, he could no longer remember why it was that he had been unable to reach a conclusion fiom the sample. He stated in the CP that he recalled explaining the difficulty to the police at the time, and that he had no reason to believe the police statement created thereafter was inaccurate.

There is a note at the foot of the precognition stating that the manuscript statement would be necessary, followed by handwriting stating “not available”. There is no defence precognition for him.

In evidence he was asked if he was successful in his attempted analysis of DP/15, and he

said that he was not, that he was not able to identify it as being manufactured by

Gould. He confirmed that he signed the label for DP/15. In Williamson’s ch10 CP

he states that the reason Lomer did not try and take another sample was because he

was not confident he would be able to get any better a result. Williamson then states

that Lomer was shown DP/14, the photographs Whitehead had produced, and at that

time Lomer agreed with Whitehead’s conclusion that, fiom the photographs, it

appeared that the copper foil had been manufactured by Gould Electronics (although

note Whitehead’s position, at CP and DP that he did not think Gould had produced the

copper, that he thought it was made in the Far East – see under 15 Feb 90 above).

This echoes Williamson’s memo of 16 March 1990, in which he said that Lomer

agreed that, based on the high magnification photos taken by Whitehead, the copper

was in all probability produced by Gould.

In Williamson’s memo to the SIO dated 16 March he stated that the two companies,

Yates and Gould, together controlled around 70% of the world market in copper foil

production, so the fact that the copper in PT/35(b) appeared to have been

manufactured by Gould was no more than of interest.

Note also that, according to Buwert’s statement S4649U, Lomer did not sign the label

for DP/10 until 23 January 1992. NB Lomer’s signature is visible on the labels for

DP/10 and DP/15. As stated, the label for DP/10 was apparently signed by him in

1992. There is no mention of him having signed DP/15 “late”.

8 March 1990

Control sample laminates tested – continuation of resin test

According to Harrower’s statement (AC) and his ch10 CP, after the visit to Ciba

Geigy on 8 February he made contact with a number of companies involved in the

production of fibreglass laminate used in the manufacture of PCBs, and obtained

samples of the various laminates they produced for comparison with PT/35(b).

He received in total 23 different sample laminates from producers in Europe and the

Middle East, which he understood covered all the production companies, and he

produced DP/143 (prod 337), a schedule showing the laminate samples and suppliers.

He provided the 23 samples to John French at Ciba on 8 March 1990 for comparative

analysis. He later obtained a statement from French of the results of the analysis

(neither Williamson nor Harrower’s statements specify when the results were

obtained from French).

According to Williamson’s memo of 16 March 1990 to the SIO another of the “other

enquiries” that was carried out was that contact was made on several occasions with

Len Pillenger of British Telecom’s quality approval dept. Mr Pillenger apparently

provided a number of sample laminate boards from a library of information and

samples that he had, and according to Williamson’s memo the samples that he

provided were valuable in comparison at the tests carried out at Ciba Geigy.

It therefore seems that Pillenger was the source of some of the 23 samples that were

tested on 8 March 1990. The exact details of these samples or the discussions with

Pillenger are not disclosed, nor are the dates of these discussions. There is no

HOLMES statement for Pillenger.

According to French’s HOLMES statement after his analysis of the various samples

he found that two types of laminate, Ditron (manufactured in Italy) and Sefolam

(manufactured in Israel) were the closest match to the spectrum obtained from DP/12,

and he provided DP/139 (in fact this should read DP/18, prod 336 – it appears that the

designations of the two spectra printouts produced by French were mistaken for each

other in the HOLMES statements, as DP/139 is the spectra printout provided on 8

February, above), a spectra printout showing the laminates listed in DP/143 that

closest matched PT/35(b).

In French’s CP he basically confirmed this account of events, but stated that he had not seen the schedule of samples, DP/143, before. He also said he tested the fragment PT/35(b) again on this second visit by police, and he said a clearer printout was achieved on this occasion. He noted from the spectra printout DP/18 that solder mask traces were found on the non-track side of the fragment.

He stated in his CP that Williamson had produced a statement and

provided a copy to him, and he had referred to this prior to the precognition. He had

very little memory of the subsequent visit by police in 1992 (see below) which would

suggest that his memories in his CP must have relied on the contents of the police

statement. According to French’s CP and DP, he provided the outcome of his

analysis in the form of a letter dated 9 March 90, and in his defence precognition he

said the police then incorporated the letter into a statement. He apparently produced a

copy of the letter at his Crown precognition.

According to Williamson’s defence precognition, “some time later” he received the information about Ditron and Sefolam, and then later he had tests carried out by Dr David Johnson at the University of Manchester (see 23 May 90, below). In Williamson’s memo to the SIO of 16 March 1990 he reported that French said the fact that PT/35(b) was exposed to extreme heat could have had an effect on the results of the analysis and that, although

Ditron and Sefolam were the closest matches, this could in no way be viewed as conclusive.

9 March 1990

Removal of 5th sample – DP/16 (Crown label n°418) – solder mask scraping – solder mask test)

Williamson and Harrower visited Morton International Dynachem Limited in

Warrington, after previous telephone contact (according to Robert Linsdell’s

statement S5585). The company produced chemicals and solder masks used in the

PCB industry. They met Robert Linsdell (S5585) (it is wrongly spelt Linsdale in

some HOLMES statements), technical manager, who agreed to analyse the solder

mask on PT/35(b). A senior analyst, Steven Rawlings (S5581) removed a solder

mask scraping, designated DP/16, from the side of the fragment which did not have

the copper tracks and land, and a spectra printout, DP/17 (prod 341, the police label

for which Harrower confirmed in his CP was completed and signed by him) was

obtained after analysis on an infrared spectrometer.

According to Linsdell’s statement he compared this with a sample two-part epoxy and

a dry film solder, and concluded that PT/35(b) had a green coloured two-part epoxy solder

mask applied during manufacture. The normal way of applying this was by screen printing

and, once on, it could not be discerned who manufactured the solder mask.

Two part epoxy solder mask was the most common. Linsdell also microscopically examined PT/35(b) and DP/11 and concluded that, on the opposite side from the copper tracks, there was evidence of copper having been scraped away, indicating that originally the board had been double-sided (i.e. copper tracks on both sides) and that solder mask had been applied to the side of the fragment without the copper tracks on it. Rawlings’ defence precognition gives more details about the tests carried out.

In Rawlings’ ch10 CP he stated that he could no longer remember for sure whether

the solder mask was on one or both sides of the fragment, but he thought it most likely

that there was solder mask on only one side as he only took one scraping. He also

stated that he would be unable to say in court for certain that the solder mask coating

on PT/35(b) was not acrylete based as it was theoretically possible that, in the event of

exposure to high temperatures, the acrylete could have decomposed leaving other

materials which suggest that it was epoxy based, as acryletes burn off at much lower

temperature than other components of solder mask. He stated that this was only a

theory, and he had not conducted any tests. He gave evidence and confirmed that the

solder mask on the fragment was consistent with epoxy solder mask, and was not

acrylate-based solder mask so was not produced by his company, Morton. He made

no mention of the doubts he expressed in the CP. He confirmed in evidence that he

signed the label for DP/16.

According to Williamson’s ch 10 CP dated 17/11/99, both Linsdell and Rawlings

concluded that the sample DP/16 was a “standard sample” and they were of the strong

opinion that the solder mask had been applied to only one side of the fragment of

circuit board.

According to Linsdell’s ch10 CP the police were interested in distinguishing the

fragment fiom a Toshiba radio board. Linsdell’s CP states that radio cassettes are

mass-produced, constructed from cheap materials and a simple design, and the

fragment was clearly different as the material was not cheap, being a professional

base substrate widely available in the circuit board market.

It is unclear why there would be any need to distinguish the fragment from a Toshiba

circuit board. In Williamson’s memo to Henderson of 16 March 1990 he recites the

history of PT/35’s discovery and specifically states that the circuit board that

controlled the Toshiba SF16 RCR was constructed of Phenolic paper, whereas

PT/35(b) was made of fibreglass laminate, so though closely involved with the debris from the RCR, it was not part of the RCR. That conclusion is also clear from various other sources e.g. RARDE report.

Linsdell’s CP states that the officers also wanted to know if the fragment was

commercially or domestically manufactured, and Linsdell felt that domestically no

solder mask would be placed on either side and the curved edge had been

professionally routed to fit a specific container, and such a neat finish would not have

been possible if they hand cut the corner, as it was very neat and strongly suggested a

machine had been used in the process. He felt the design was constructed in a

professional shop but the design was not suitable for mass production, rather would be

used to construct 20-30 samples. [This all seems accurate when compared to the set

up at MEBO and the no. of timers they produced, but there is no record of these

opinions in Linsdell’s HOLMES statements.] He explained that Rawlings was the

expert analyst and he was not qualified to speak to the analysis carried out on DP/16.

He confirmed he had signed the label for this sample. Note however that according

to the statement of Rolf Buwert S4649U, he arranged for Linsdell to sign the label for

DP/16 on 14 January 1992.1 He could not recall examining DP/11 by microscope but

accepted that if his police statement said this, it was likely to be more accurate than

his recollection. He was asked why a board manufacturer would put solder mask on

the non-track side of a board and not the track side, and he accepted that this would be

unusual, suggesting that the solder mask gives the board a more professional look so

if the non-track side is exposed to view, that might be the reason. As noted below

(see under 17 May), at CP Linsdell was shown DP/141, Williamson’s report on the

fragment, and saw nothing wrong with the terms of it, despite it saying that the board

was solder masked on both sides, whereas Lmsdell at CP stated that it only had solder

mask on the non-track side. At the end of the CP there is another PF’s note which

indicates that the police statements overstated Linsdell’s role in the examination and

that he was not qualified to speak to the tests, which were done by Rawlings. Only

Rawlings gave evidence, Linsdell did not.

NB Linsdell examined the fragment again on 14 June 1990 at the PCB industry

convention at the SECC (below).

NB Linsdell and Rawlings were also seen by police in 1992 and asked to examine a

control sample MST-13 circuit board – see 2 March 1992 below. NB The signatures

of Linsdell and Rawlings are visible on the label for DP/16. As stated below, it seems

that Buwert arranged for Linsdell to sign the label “late”, on 14 January 1992. There

is no indication that Rawlings signed the label later, and the position of his signature

might indicate that he did not sign it late. The signatures of both do not appear to be

on the label for PT/35(b).

13 March 1990

(“other enquiry” i.e. not evidentially significant)

According to Williamson’s memo of 16 March 1990 to the SIO another of the “other

enquiries” that was carried out was that contact was made with Mr Denham of the

International Tin Research Institute, Uxbridge, on 13 March 90. He stated that after

the tin had been plated onto a board there was nothing that could be analysed in the

tin which would be worthwhile. He could not analyse the depth of the tin coating on

the fragment as he did not have the equipment to do so, but recommended that contact

be made with a company which had a Fischer scope X-ray. There are no HOLMES

statements for Mr Denham.

Also on 13 March 90, another of the “other enquiries” was carried out, that being that

contact was made with a Mr Haken of the Printed Circuit Board Federation in

London. He knew of no list or information available on companies using tin as an

etch resist but suggested publishing all available information on the fragment in the

monthly newsletter, and in the equivalent newsletters for Europe and the USA. There

are no HOLMES statements for Mr Haken, and no indication that the steps he

suggested were implemented.

(Some time prior to) 16 March 1990

“other enquiry” i.e. not evidentially significant

According to Williamson’s memo of 16 March 1990 to the SIO another of the “other

enquiries” that was carried out was that contact was made with several clock

manufacturers in the UK to establish the type of product being manufactured and the

type of circuit boards which would be contained in any clocks produced, but it was

learned that there are no companies in the UK actually manufacturing clocks

[presumably this means there are no companies manufacturing the PCBs for clocks],

all are imported from abroad.

The date of contact with the clock manufacturers is not specified, but it must have been prior to the writing of the memo on 16 March 1990.

However, it is noteworthy that although the memo is dated 16 March, in fact it seems

that the memo has been added to after that date, as there are various references to the

removal of DP/31 and to information obtained from Allan Worroll, all of which

occurred after this date (see below).

In a separate section of Williamson’s memo headed “Further lines of enquiry

considered” he states that contact had been made with Underwriters Laboratories

(UL) in the USA via the Explosives Laboratory at the FBI, but they indicated that the

only way of identifying the board would be from unique markings on it. The memo

suggests that there are no unique markings on the fragment so it would be highly

unlikely that UL would be able to progress the enquiry. There are no further details

about this enquiry or about who exactly it was who was contacted at the FBI’s

Explosives Laboratory.

The memo also mentions that Dr Colin Lea at the National Physics Laboratory was interviewed and allowed to examine the fragment and he doubted that identification would be achieved via chemical analysis. His suggestion was that a photo and detailed description of the fragment be published in PCB inhouse journals and that to generate interest reference should be made to the Lockerbie disaster.

There is no HOLMES statement for Dr Lea, nor any other information to indicate that this was course of action was followed, although no doubt the enquiries were confidential at that stage. It is not specified when Dr Lea was interviewed.

As mentioned in the preceding paragraph, although the memo is dated 16 March 90 it

was clearly added to thereafter.

11 April 1990

No samples removed, but DP/11 re-potted.

By previous appointment, Williamson and Harrower met Allan Worroll (S5586),

chief chemist at Ferranti Computer Systems, Oldham, who examined DP/11

microscopically and suggested further tests that could be done at Manchester

University, and it was agreed that the officers would return at a later date to have

these test carried out (in Williamson’s ch 10 CP dated 1711 1/99 he said that Worroll

was unable to arrange an appointment with Manchester Uni immediately, hence the

agreement that the tests be carried out at a later date). Worroll’s HOLMES statement

goes into more detail about what he saw, stating that he saw PT/35(b) and the curved

edge appeared to be professionally milled; and there were two edges which were

broken off and charred as if exposed to heat (in his ch10 CP Worroll stated that he

was in no doubt the fragment was heat damaged and he had seen such an effect before

in his career, as accidents did happen); solder mask had been applied to both sides of

the board. He also examined DP/11 and noted that its position in the potting made it

difficult to examine, so he re-potted it and reground it to facilitate better optical

viewing.

He confirmed that the board was made of fibreglass laminate constructed

with nine layers of glass cloth and the board appeared to be single-sided (i.e. copper

tracks on only one side) as there was no evidence of “through hole plating” (in his

ch10 CP Worroll stated that his view that it was single-sided because there was no

evidence of through hole plating was “simply instinct”, as there was no circuitry on

the reverse of the fragment). He suggested that there was solder mask on both sides

of the board and stated that this was a mystery as he could see no reason for the

application of solder mask to both sides of a single sided printed circuit board. The

suggestion that the board had solder mask on both sides is contradicted by other

witnesses (see 9 March above and 14 June below; the RARDE report also suggests

that the board had solder mask on one side only; in his ch10 CP Worroll himself said

it was only solder masked on one side – see in this section below). Worroll then

refers to being told by police that previous examination had revealed that the copper

tracks were lined with tin only as opposed to a tin/lead combination which would be

more normal, and that previous examinations had most closely matched the fragment

to two samples, and Worroll suggested that he make arrangements with the Dept of

Science and Technology at the University of Manchester, which could use Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry test equipment to very accurately tell if the fragment matched

the two samples. According to Harrower’s ch10 CP, as a result of the discussion with

Worroll and a suggestion made by him that they pursue the construction of the

conducting tracks, as they appeared to be pure tin rather than a mixture of tin and

lead, the police went to Siemens, Munich (see below).

Williamson’s memo to the SIO dated 16 March 1990, which was clearly updated after

that date, also mentions that Worroll had identified some evidence, a long scratch-like

mark, across the large pad on the fragment, which suggested that a thin insulated wire

could have been soldered to the pad, there being the part profile of a wire having been

laid across the pad when partial fusion of the tin occurred leaving the impression of a

thin wire lead. This might be consistent with what Williamson’s memo records Dr

Wilkinson as having seen – the cylinder which she thought could have been the

remnant of where a wire had been embedded in the solder. (see under 2 March 1990, above)

In his defence precognition Worroll states that the police were interested in knowing

if the fragment came from a board made on a production type process or if it could

have been the work of an individual working alone using more basic procedures, and

Worroll’s view was that the general finish and machining of the fragment, the

appearance of the metallic circuitry and the constituent substances used, including the

fact that the solderable finish was tin and lead as opposed to just tin, made Worroll

think it was from a production line process. His ch10 CP refers to this question of

whether the fragment was manufactured commercially or not, and he says that he had

looked at a cross-section of the tracking to see the track profile, as commercially

produced tracks tend to be clean and almost vertical, whereas domestic manufacture

tends to have a sloping profile. He suggests that the examination he carried out was

inconclusive, the track profile was fairly good, suggesting commercial manufacture,

but he could not discount that it was done domestically by an expert. He later refers

to the curved edge having been machined rather than hand cut. The PF in a note

stated that this contradicted Worroll’s original statement (in that he originally said the

track profile suggested it was a homemade board, although the milled curve was

indicative of professional manufacture). Worroll examined PT/35(b) and confirmed

he had signed the label. He stated that from this examination he could confm that

the solder mask appeared only on the reverse side, and said this was apparent due to

the green appearance of that side. He said it was unusual for a board to have solder

mask on the reverse side as it is normally used for protecting tracking and circuitry.

He could not think of any reason for it to be applied on the reverse side. He examined

DP/11 and said it bore the hallmarks of his work although he could not recall why the

fragment had been cross-sectioned at the particular angles they had been. Worroll

gave evidence but it added little to what is noted here, and the terms of his evidence

were rather vague: Worroll seemed still unable to recollect that he had removed the

solder mask from DP/31 (see 23 May 90, below) and appeared to get confused about

what he was being asked. He did state in evidence that solder mask was only visible

on one side of the fragment.

Worroll’s statement and the police report have this first visit to Ferranti dated 11 May

90, but Williamson and Harrower’s statements date it at 11 April 90. Worroll’s

statement refers to the police attending on a second occasion on 23 May 90 (below)

and being advised that since the last visit, DP/31 had been removed from the fragment

by Siemens. As the removal of DP/3 1 occurred on 27 April 90, it would suggest that

the first visit to Ferranti was before that date, which would indicate that 11 April was

the correct date for this first visit. Also, Worroll’s statement concurs with those of the

officers by referring to the day of the first visit as a Wednesday. In fact 11 April was

a Wednesday but 11 May was a Friday, again indicating that the earlier date is the

correct one.

As stated above, according to the CP and DP of Paul Boyle of New England

Laminates (see under 14 February above) he was visited again by police who had with

them DP/11, which by this stage had been altered. It seems apparent that, assuming

Paul Boyle is correct in his memory (which it seems he must be, given that DP/11 was

indeed altered by Worroll) then this return visit to see Boyle must have been after

Worroll had altered the position of DP/11. As stated above, there is no record of this

return visit to New England Laminates.

NB Worroll was also seen by police in 1992 and asked to examine a control sample

MST-13 circuit board – see 5 March 1992 below. NB Worroll’s signature is visible

on the label for DP/11 and for PT/35(b).

27 April 1990

Removal of 6th sample – DP/31 (Crown label no.419) – large corner cross section

According to Williamson and Harrower’s HOLMES statements, in the course of the

various examinations the most unusual feature about the fragment was said by the

experts to be the application of pure tin to the conducting tracks, as opposed to a

tin/lead combination, and the statements indicate that the officers had been advised

that Siemens in Munich could assist with examining this aspect of the fragment (it is